late bloomer

Twenty years ago, I thought I was about to be a late bloomer. I was going to write my very first novel. I had written short stories and poems in my teens and early adulthood—mostly unpublished, mostly not even submitted. At fifteen, inspired by Françoise Sagan’s runaway French sensation Bonjour Tristesse, I imagined I, too, could write a shockingly semi-salacious story about a youth and an older seductress. I wrote something, but even then I could tell it lacked verisimilitude and anything vaguely approaching literature.

Skip ahead to my senior years. After a very brief career as a dancer and a long career as a psychiatrist, I picked up the virtual pen and began to write again. At the same time, two friends—both men as long in the tooth as I—were embarking on new careers as painters, one after working as a dealer in Asian antiquities, the other as a commercial graphic designer. Then I had the idea for another book, one about such late bloomers: a potentially rich story about people well past the usual age of so-called “late” bloomers, most of whom, as the literature revealed, were only in their forties. My cadre were in their sixties and seventies—ages associated with rocking chairs and imminent death. I thought I was discovering a new niche. I began to search for others.

Meanwhile, I was making genuine headway in the novel that had inspired all this. And after a strangely fallow fifteen-year period, the novel is now finished and titled Father ∫ Son.

So what prevents the very late bloomers from blooming?

What I encountered—roaming around my usual mix of social media, personal and public—was a new experience of blank-out. Now, in my eighties, my role, no matter how defined, and no matter any accumulated wisdom or expertise, no longer seems to enjoy relevance. It’s as if attention can no longer be paid; as if I’ve been assigned a silent rocking chair to occupy while others turn a deaf ear. I wonder if this is a genetically installed response to extreme old age, preparing younger survivors for the overlong, overdue survival of those who outlive and now alienate them. It resembles retirement mandates that declare workers no longer qualified, no longer fit, no longer in possession of useful wherewithal.

The result of being—not intentionally but constitutionally—overlooked is a sense of isolation and disregard that makes one feel enfeebled.

What to do? Find cohorts? Use online media while blanking out references to my age—go ageless? At minimum that would involve adopting some of the new language of that medium and communicating about topics that relate to the unretired.

Another strategy might be finding an age-related consortium—but only to rail against the exclusionary state we share? Or at best to invent ways to reanimate our lives?

Getting very old, even when health is somehow a non-issue, is a new and unanticipated challenge. Reclaiming relevance becomes a hidden fundamental need that moves to center stage in a way slightly parallel to adolescence. Being a teenager often feels like no one will listen, no one will take you seriously. But then come the long adult years when who and what you are does count.

In this post-retirement age—past the activities that once held relevance—in this new “dead-person-walking” era beyond eighty, achieving appropriate and acknowledged relevance becomes the central challenge.

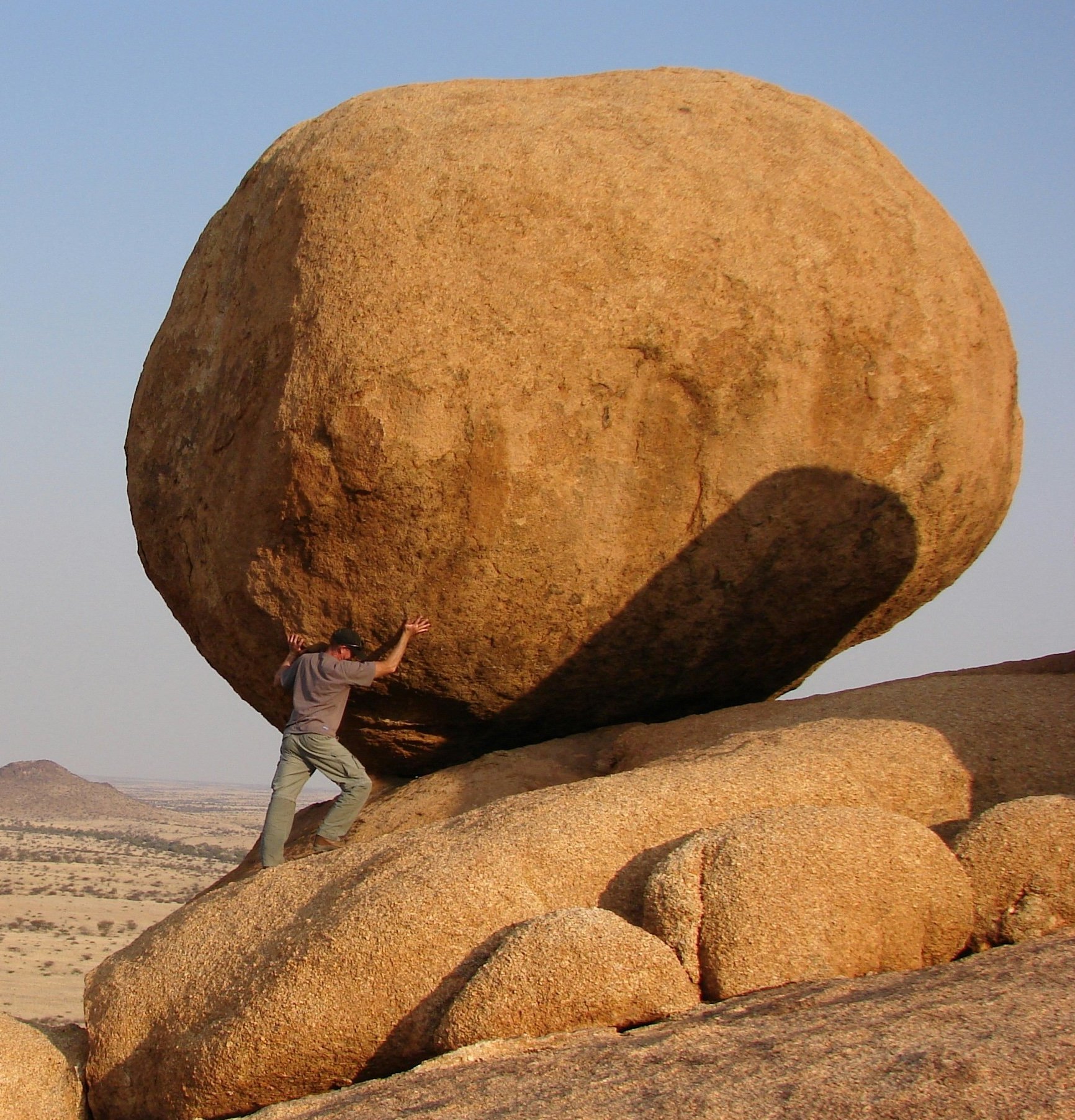

Think of it as being a teenager again, only aged in the cask like whiskey: with deeper flavor, stronger presence, and a bite that lingers.